The story starts with Buster, an 18-month-old tabby cat in Schenectady, New York. In 1997, 16 year old Chester Williamson poured kerosene on Buster and set him on fire with a cigarette lighter. Severely burned, Buster lived in agony for weeks before succumbing to his injuries. At the time animal cruelty toward a pet like Buster was legally as a misdemeanor, and there was no meaningful law enforcement infrastructure to punish such crimes. The public outrage, however, birthed Buster’s Law in 1999, creating a felony in New York: Aggravated Cruelty to Animals. The law’s text defines it as intentionally causing serious injury or death to a companion animal, “with aggravated cruelty,” meaning acts intended to inflict extreme pain, or carried out in a sadistic, depraved manner.

Buster’s Law was supposed to mark a turning point. But as you know from the leaks and other cases we have covered, laws chase after the offenders but seldom catch them at full force. Even under Buster’s Law, prosecutors often downgrade cases, charges slip, plea bargains water down justice. The law had promise, but it also carried limited penalties and no mechanism to track or block abusers.

A 2011 Times Union investigation found that between January 1, 2005, and November 22, 2010, there were 373 arrests under Buster’s Law. Only 63 resulted in felony convictions. Another 112 produced misdemeanor convictions, and 39 led to non-criminal pleas. That means well over half were never convicted of a significant crime. Worse, among those who did get convicted, only 94 defendants statewide served any jail or prison time. In many cases, the sentence was only probation or a fine. Even in the Capital Region, out of 12 convictions only 4 resulted in any jail time.

New York is now seeking to create a statewide animal abuser registry. The goal is to make sure convicted offenders can’t just move to another county, change their name, or quietly adopt from an unsuspecting shelter. The proposed registry would make felony animal cruelty convictions public and searchable, and it would back them up with tougher penalties, longer bans on animal ownership, and mandatory psychological evaluations before someone can ever own a pet again. In theory, it’s the missing piece Buster’s Law never had. Not just punishment after the fact, but prevention… a way to keep repeat offenders from slipping through the cracks.

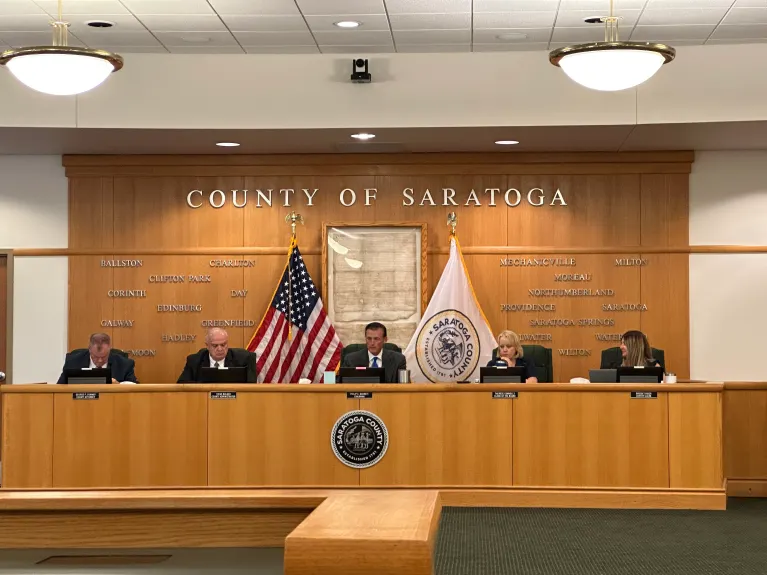

The push for a statewide registry isn’t coming out of nowhere. Local governments have already been filling the gap on their own. As of this year, Saratoga County became the 26th county in New York to approve its own animal abuser registry, joining Albany, Rensselaer, all five New York City boroughs, and others. Under Saratoga’s law, anyone convicted of animal abuse crimes will have to register their name, address, and photo with the county within ten days of conviction or release. The listing stays up for 15 years on a first offense and becomes permanent if there’s another. Shelters and pet sellers are legally barred from handing over animals to anyone on the list, and failure to register carries up to one year in jail and $1,000 fines for each day of noncompliance.

The county board passed the law unanimously, citing a string of recent abuse cases involving dozens of neglected or tortured animals as proof this couldn’t wait. As county officials pointed out, there’s a patchwork problem here, someone on the Saratoga list could drive to a neighboring county without a registry and adopt a pet tomorrow. That’s why both the county’s public safety committee and state lawmakers are now pushing for a single, statewide registry to close those gaps.

Alongside the registry effort, legislators are now backing the Safe Pet Boarding Act, the first statewide law to set standards for boarding facilities in New York. It comes after a summer of headlines about dogs dying in overheated kennels, including 21 animals left in a building with no water or ventilation for 11 hours. The bill would require boarders to register with the state, pay an annual licensing fee, undergo random inspections, and follow rules on heat, feeding, sanitation, and safety. Facilities that fail to comply could face fines, license suspension, or closure.

Both the registry and the boarding bill reflect the same shift… moving beyond punishment alone and trying to prevent cruelty before it happens. It’s a long way from Buster’s Law, and maybe the start of a system that doesn’t wait for animals to suffer before acting.

Chester Williamson was convicted of sexual abusing a 12 year old girl in 2008, he is designated a sexually violent offender.